Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Henry Woodward comes into history as a twenty-year-old on June 22, 1666 aboard the ship Berkeley Bay on a voyage of exploration with Lt. Col. Robert Sandford. They along with twenty others in two small ships had sailed south from a colony established on the banks of the Cape Fear River a few miles north of today’s Wilmington, North Carolina. Founded in 1663 primarily by Barbadian sugarcane planters, the colony was intended to be a place to expand their agricultural endeavors. But due to Indian conflicts and hidden shoals in the river that made shipping difficult, the colony was struggling and needed to find a new home.

One could imagine Woodward leaning on the rail of the Berkeley Bay as the sun stood high in a cloudless sky and feeling a strange sensation that these islands of live oak forests and palmettoed beaches were where his life would take a profound turn. Scanning the expanse of lush foliage, concentrating on what he was seeing, not speaking to anyone, he hungered to take in the essence all that these verdant, unspoiled islands had to reveal.

The next day Sandford anchored the Berkeley Bay four miles up a river between two islands which were later named Seabrook and Edisto. The river was later named the North Edisto. He then went in a smaller shallop which had accompanied his ship and explored up a large creek – Bohicket Creek – and landed at a point of land on what is now near the town of Rockville, South Carolina on Wadmalaw Island. As Sandford later wrote in his report to the Lords Proprietors when he returned to Cape Fear, it was there that he “tooke a formal possession by turf and twig of that whole country from the Latitude of 36 degrees North to 29 degrees South and West to the South Seas by the name of the province of Carolina for our Soveraigne Lord Charles the Second, King of England and his heirs and successors…” (His report should have read 29 degrees north. 29 degrees south latitude would actually be in South America.) Although both France and Spain had formerly laid claim to this land and Spain still considered if part of Spanish Florida, as far as Sandford, and the eight Lords Proprietors who had financed the Cape Fear settlement, were concerned, it now belonged to England.

Sandford then proceeded south charting the coastline and exploring the numerous rivers and creeks he encountered. Then on the third of July, Sandford sailed his small fleet into a wide sound that in 1562, French explorer Jean Ribault had called “one of the greatest and fairest havens in the world” and named it Port Royal.

The next morning, he anchored opposite an Escamacu Indian village located on a tidal creek near the southern tip of what is now Parris Island. Indians living in the Port Royal area were already familiar with Europeans coming to their shores. For over 140 years, beginning in the 1520s, Spanish explorers and slave hunters, Catholic priests, French Huguenot settlers in the 1560’s, William Hilton in 1663, and other European explorers and fishing vessels had plied the coastal waters.

In spite of all of this activity, however, there were no permanent European settlements from St. Augustine, Florida to the small colony at Cape Fear. The only visible European influence in the Port Royal region were a few small, scattered missions set up by Spanish priests, and in the Escamacu village a “faire wooden Cross of the Spanish ereccon” which the Indians seemed to ignore.

For several days, Sandford, Woodward, and their shipmates traded with the Escamacu gaining their trust and observing their customs. Like other Indians up and down the coast of America, the Escamacu were pleased to get such things as knives, cooking utensils, and other metal items and traded deerskins, furs and food the English desired.

Then on the night of July 7, just as Sandford was preparing to weigh anchor and sail back to Cape Fear, Nisquesalla, the cassique or chief of the Escamacu brought his nephew on board the ship and asked if the boy could accompany Sandford back to Cape Fear in order to learn the English language and way of life. Three years earlier, Nisquesalla’s son, Wommany and another Indian named Shadoo had traveled with Captain William Hilton to Barbados and apparently the uncle wanted his nephew to have the same experience. Sandford agreed and told Nisquesalla he would sail tomorrow and return in ten months.

In order to reciprocate this gesture of friendship, Henry Woodward, who Sandford described as a “Chirugean” (surgeon) saw a great opportunity to experience this lush land and its people. He informed Sandford that he would like to stay with the Escamacu until Sandford returned. Sandford agreed to the exchange.

The next day Nisquesalla welcomed Woodward to his village by giving him a field of maize and assigning his niece, the sister of his nephew who was sailing with Sandford to “tend him and dress his victuals and be careful of him soe her Brother might be better used among us.”

Since Sandford had claimed this territory for England, and Woodward was to be the first English inhabitant, Sandford gave Woodward “formal possession of the whole country to hold as Tennant att Will of the right Honorable the Lords Proprietors.” Thus, Henry Woodward became the sole English tenant of all that is now South Carolina and “West to the South Seas.”

Although Woodward did not keep a journal of his life among the Escamacu, he later reported that he made strong friends among his generous hosts, and he learned their language well enough to become interpreter and primary trader for the English settlers who would establish a colony on the Ashley River in 1670. A fortunate circumstance was that the language spoken by the Escamacu was the same spoken by the other Cusabo Nation tribes that occupied the rivers and estuaries from Port Royal to Sewee Bay northeast of today’s Charleston. Thus, in three years when English settlers landed in the territory of the Kiawah, Woodward could converse with these natives.

It is interesting to note that little is known about Woodward’s early life, and no one is sure where Henry Woodward got his medical training. Some have speculated that he was born in England where he attended medical school and at age 19 sailed to Barbados. Others contend that was born in Barbados and had traveled to England as a teenager and received medical training there. Or perhaps a physician at Barbados had instructed him. What is known is that as early as age twenty, he was known as Dr. Woodward, “chirurgeon” to Robert Sandford and others.

Having an opportunity to stay with the Escamacu was a very fortuitous coincidence. As one historian wrote, Henry Woodward came to the Indians with the pride and background of an Englishman and the courage, idealism, and curiosity of youth. He wanted to learn the Indian language and lifestyle, make himself a better doctor, and bring peace where in the past there had been conflict. It was said that like Sir Walter Raleigh, he possessed a multifaceted mind, and like Captain John Smith, he wanted to get to the essence of the new land and its people.

After several months with the Escamacu and their neighbors, Woodward was discovered by the Spanish and taken under arrest to St. Augustine, Florida. As an Englishman trespassing on what the Spanish considered their territory, Woodward was put in prison. Once it was learned, however, that he was skilled in medicine and healing, he was put in the custody of a priest and was able to move freely about the town.

Henry was apparently well treated by the Spanish in St. Augustine. He learned the language, and it is speculated that he joined the Catholic Church there. Yet, when the opportunity came for him to rejoin the English, he took it.

The opportunity came on a night in May 1668 when English privateer Robert Searle and his crew raided and plundered St. Augustine. In the noise and confusion of the attack, Woodward found Searle and sailed away with him on his ship, Cagway. For the next several months, Woodward served as ship’s doctor for Searle and other privateers as they searched the Caribbean for Spanish treasure ships.

Luck intervened again in Woodward’s life on August 17, 1669 when a hurricane wrecked the ship he was on near the coast of Nevis, one of the leeward islands in the West Indies. Woodward and most of the crew escaped and took up residence on the island.

By coincidence, almost the same day as Henry went ashore on Nevis, three ships: The Carolina, The Port Royal, and The Albemarle loaded with 150 passengers and supplies left England intent on establishing a colony at Port Royal. Favorable reports by William Hilton and Robert Sandford had convinced the Lords Proprietors of the suitability of the area based on the fertility of the soli and the fact that the Indians were friendly and helpful. Indian hostility had been one of the main reasons why the Cape fear colony had not succeeded.

The fleet’s first stop was at Barbados to pick up more passengers and supplies. All three ships left Barbados on November 2. As they sailed north through the Caribbean, a storm forced the ships to stop at Nevis until the weather improved. It was at Nevis on December 9, 1669 that the colonists ran into Henry Woodward who asked to accompany the expedition to Port Royal. With his request granted, Woodward was now on his way back to the area where his Carolina adventure had started three years earlier.

After leaving Nevis the fleet stopped at Abaco in the Bahamas. While at anchor at Abaco, The Albemarle was damaged beyond repair by high winds and was replaced by another ship, The Three Brothers. Both The Carolina and The Port Royal were damaged but were repaired. While The Three Brothers was being prepared to sail, The Carolina and The Port Royal set sail for Bermuda. On the way north from Abaco, The Port Royal was blown off course and wound up in southern Virginia.

The Carolina then sailed on to Bermuda and arrived there in February. After a few days, the colonists headed west but got off course and wound up at Cape Romaine, several miles north of Port Royal. Here they encountered the Sewee Indians and a Cassique who was visiting them from the Kiawah tribe.

The Cassique of Kiawah proved to be an intelligent fellow who had a good knowledge of the Carolina coast. He requested that he be allowed to sail to Port Royal with the English, and Captain Joseph West was happy to grant his request. With the help of the Kiawah chief, West soon got his bearings and sailed the ship south to Port Royal.

All was not well at Port Royal, however. The colonists were told by the local Indians that a renegade Indian tribe, the Westo had moved into the area and were causing trouble. The Westo, an Iroquoian tribe that had migrated to the Savannah River from Virginia, had recently raided the Escamacu village and kidnapped several people who the Escamacu believed were sold to slave traders in Virginia. The remaining Escamacu no longer felt safe there and were planning to leave the area.

After hearing about the problems caused by the Westo, the Cassique of Kiawah strongly suggested that the English sail north to his territory and establish their settlement there. William Sayle, who had been appointed governor of the proposed colony agreed. With the Cassique aboard, Joseph West sailed the Carolina north until they came to a wide river that three years earlier Robert Sandford had named the Ashley after Anthony Ashley Cooper who was at that time the most enthusiastic of the eight Lords Proprietors about establishing the English colony in Carolina.

Finally, in April 1670, after seven stormy months at sea, some 100 men and women aboard the Carolina sailed into a creek on the west side of the Ashley River and dropped anchor. The spot had been chosen because it could not be seen from the sea and would give the settlers some protection from the Spanish ships that occasionally sailed up from St. Augustine and patrolled the area.

Now the business of building homes, planting crops, coping with the heat and humidity, the bugs and wild animals, the Spanish to the south, and the Indians all around them could begin. A few weeks later, The Three Brothers which had replaced the storm-damaged Albemarle, arrived with another 50 settlers and the little colony began to grow.

It was at this time that Henry Woodward’s experience with both the Indians and the Spanish became valuable. After so long at sea, supplies were running low, and the first crops planted would not be edible for several months. One of the ships was sent to Virginia for supplies, but again the round-trip journey could take weeks. The settlers had to turn to the Indians, and Woodward was the only person in the settlement who could speak their language well enough to trade for the food and supplies needed.

The ships had brought along trade goods, everything from knives and hatchets to cloth, mirrors and glass beads, and with these items Woodward was able to trade for enough food to meet the short-term needs of the colony. He then turned his attention to establishing a long-term trade in furs and deerskins that would become some of the colony’s main export items to use in commerce with England.

Not long after helping the colonists get on their feet and settled in, Henry began in earnest to explore the wilderness beyond the bounds of the small but growing colony first called Kiawah after the Indians living in the area, then Albemarle Point after George Monck, Duke of Albemarle, one of the Lords Proprietors. A few months later the name was changed to Charles Towne in honor of King Charles II.

A word on the Lords Proprietors who financed the Charles Towne colony: After the death of Oliver Cromwell in 1658, there began a movement in England to restore the monarchy by bringing out of exile the son of the deposed King Charles I, Charles II. Eight prominent politicians and military leaders were involved in the scheme that resulted in Charles II, who was 30 years old at the time, being crowned King of England in 1660.

Charles rewarded the eight by giving them titles and the right to establish colonies in America. They were: Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftsbury; Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon; George Monck, Duke of Albemarle; William Craven, Earl of Craven, John Berkeley, Baron of Stratton; William Berkeley, governor of Virginia; Sir George Carteret; and Sir John Colleton.

The idea was that as proprietors of new colonies, they could profit from the venture by controlling exports from the colonies and charging rent on the land the colonist lived on and farmed. Although the first colony at Cape Fear did not succeed, the colony at Charles Towne did. Today, a number of counties, rivers, roads, and waterways in both North and South Carolina are named after the Lords Proprietors.

Woodward, who knew the Cusabo language from his time with the Escamacu, quickly established good relationship with the Indians along the Carolina coast. Albemarle Point became a busy trading center. In the last few years, archaeologists have discovered a number of items from beads to cooking utensils in the area of the landing site.

Nor did it take the Spanish long to discover the Charles Towne colony and make an attempt to destroy it. In August 1670, three Spanish ships with soldiers and other smaller vessels manned by Indians were spotted a few miles south of Charles Towne by some Stono Indians, a Cusabo tribe which Woodward had befriended. They warned the colonists and the militia was alerted. Shots were fired to stave off the attackers. The show of force by the colonists worked and the Spanish retreated back to St. Augustine.

A few months later, Woodward related in a letter to Sir John Yeamans, a Barbadian planter and a backer of the colony, that one of his first long journeys was north to the powerful Indian town of Chufytachique some “14 days travel after ye Indian manner of marching.” Believed to have been located a few miles south of present-day Camden, South Carolina, Woodward described it as “a Country so delitious, pleasant and fruitful, yet were it cultivated doubtless it would prove a second Paradize.” While there, Henry met the chief and other leaders of the nation and not only procured food and supplies needed by the colonists, but found a bountiful source of furs and deerskins as well.

That the leadership of the struggling colony was appreciative of Woodward’s efforts is evidenced in a letter dated September 11, 1670 written to the Lords Proprietors and signed by Governor William Sayle and five members of the governing council: William Scrivener, Florence O’Sullivan, Joseph West, Ralph Marshall, and Joseph Dalton.

Among the many complimentary things said about Woodward in the letter was that: “The Doctor hath lately been exceeding useful to us in the time of scarcity of provision, in dealeing with the Indians for our supplys who by his meanes have furnished us beyond our expectations…” They later wrote of him that “he being the only Person by whose means wee hold a faire and peaceable Correspondence with the Natives of the Place.”

For his good work, the Lords Proprietors sent Woodward 100 English pounds, a large sum in those days. A while later, Anthony Ashley Cooper appointed Henry his deputy at Charles Towne and gave him a percentage of the profits from the fur trade, a move which angered some of the other traders who were in competition with Woodward.

Through Woodward’s efforts, relations with the coastal Indians were friendly and productive. The money earned from the export of deerskin and furs along with “ships stores” such as lumber and tar became the backbone of Charles Towne’s economy.

There were, however, a few unpleasant incidents that Henry had little control over, such as when a group from the small Stono tribe of the Cusabo killed some cattle which were grazing in an area the Stono claimed as theirs. Also a few skirmishes were brought on by unscrupulous traders who used rum or coercion to cheat the Indians. And, of course, as the colony’s population increased and more land was needed, territorial disputes arose.

The tribe of Indians that caused the most concern was the one whose reputation forced the colonists to not settle in the Port Royal area. This was the Westo tribe whose fierceness terrified the less belligerent Cusabo tribes and caused the colonists a great deal of concern. They supposedly had moved south from Virginia in the 1660s and established villages along the Savannah River in the area of present-day Augusta, Georgia.

In the spring of 1670 they had raided the Escamacu and other Cusabo tribes and kidnapped a number of Indians which the Escamacu believed were sold to Virginia traders. The traders had provided the Westo with rifles and ammunition and paid a good price for young Indians who they sold to plantation owners.

In October 1674 Henry Woodward met ten Westo who had traveled to within a few miles of Charles Towne. Apparently, they had heard of the great English trader and wanted to establish a market for their furs and slaves that was closer than Virginia. Although a little apprehensive, Woodward decided to travel with them to their main village Hickauhaugua to discuss trade arrangements.

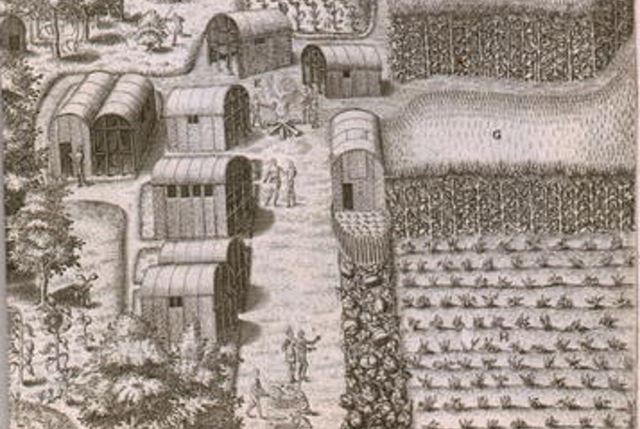

In an account of the journey written December 31, 1674, Henry described the town he visited as “built in a confused maner, consisting of many long houses whose sides and tops are both artifitially done with barke uppon ye tops of most whereof fastened to ye ends of long poles hang ye locks haire of Indians they have slaine.”

Obviously, the Westo were not a peaceful people, but in spite of the intimidation of the “locks of haire” and other signs of their warlike nature, Woodward was able to negotiate a trade agreement with them for “deare skins, furrs, and young slaves.”

That last item, “young slaves,” has caused some concern over the years. Since the voyages of Spanish slave traders Gordillo and Quexos in 1520, Indian slavery had been an unsavory but accepted practice in parts of America. There is no firm evidence That Woodward ever delt in Indian slaves himself, but there were others in Charles Towne who had no moral compunction in making a profit through the buying and selling of slaves, both Indian and African.

Several of the Carolina settlers had been planters on the island of Barbados where slave labor was used extensively to grow and harvest labor intensive crops such as sugarcane and tobacco. So, a good many of them brought their African slaves with them to clear the fields and work the plantations they were establishing in Carolina. It is interesting that the local planters were hesitant to use locally captured Indians because of their tendency to run away. Most of the captured Indians were shipped to the West Indies.

The Lords Proprietors, especially, Anthony Ashley Cooper opposed the Indian slave trade. Cooper stated his position clearly when he wrote: “Noe Indian upon any occasion or pretense whatsoever is to be made a slave, or without his own consent be carried out of the country.” Woodward shared this opinion. He knew that kidnapping Indians or buying them from raiding parties instigated by unscrupulous traders would eventually lead to problems.

It turned out he was right. Several conflicts, culminating in the bloody Yemassee War of 1715 were largely caused by ill feelings brought on by Indian slavery. Yet, in spite of the problems caused by the Indian slave trade, a group of independent-minded Barbadians who had settled in the Goose Creek area north of Charles Towne – a group that came to be called the Goose Creek men – felt as if the Lords Proprietors had no business criticizing their attempts to earn money through selling Indian slaves, and they ignored Cooper’s directive on the matter. In fact, as early as 1671, a group of Cusso Indians from a tribe north of Charles Towne were captured and shipped to plantations in the West Indies.

The conflict over Indian slavery as well as other political and economic issues, led to the development of two factions among the colonists. The followers of John Yeamans, Maurice Matthews, James Moore, John Boone and a number of the Goose Creek men wanted to break away from the restrictions imposed by the Lords Proprietors. On the other hand, Woodward and most of the other colonists felt as if Anthony Ashley Cooper and the proprietors had a right through the Fundamental Constitution drawn up by Cooper’s secretary, the philosopher John Locke, to make some rules that would facilitate the prosperity of the colony and maintain good relations with the Indians. Even though Indian slavery became a political issue, many of the colonists, including Henry Woodward, owned African slaves.

Since John Yeamans, who had become governor of Carolina after the death of William Sayle in 1671, sided politically with the defiant Goose Creek men, the Lords Proprietors replaced him with Joseph West, the ship captain who had brought the colonists safely to Charles Towne. Most of the colonists, including Henry Woodward, were pleased that Yeamans, who many considered greedy and overly profit-minded, was replaced.

One can imagine that in the politically factious atmosphere of Charles Towne Woodward would have had his share of troublesome encounters. Two incidents stand out as especially potentially dangerous. In the first, a number of traders were angered that Anthony Ashley Cooper had given Woodward special rights to trade with the Westo and other tribes and that he was being given a higher percentage of the profits than some other traders. Traders opposed to him accused him of instigating an Indian uprising and had him arrested. The Lords Proprietors allowed him to travel to London to plead his case. He not only convinced the proprietors of his innocence, but returned to Charles Towne with increased prestige as an important trader and negotiator.

Another incident occurred in 1685 involving a Scottish settlement which had been established in the area of what is now Beaufort, South Carolina near Port Royal Sound. In November 1684 a group of 148 Scots Presbyterians under the leadership of Henry Erskine, Lord Cardross established a settlement which they named Stuart’s Towne. One of their first moves was to claim a monopoly on all of the Indian trade in the Port Royal area.

At that time one of the tribes living in the area were the Yamassee which Henry Woodward had already set up trade with before the Scots arrived. In May 1685 on one of his trips to trade with the Yamassee, Woodward and his four companions were arrested for trespassing when they entered territory that the Scots now claimed as their trading area. The arrest caused a great stir in Charles Towne and with the Lords Proprietors, and Woodward was released in a few weeks.

The Spanish in St. Augustine, Florida also took note of Woodward’s arrest. Although they considered Woodward a strong competitor both politically and economically, the incident alerted them to the potential danger of having the Scottish settlement in territory they still claimed as Spanish Florida.

The incident caused two forms of retaliation, one by Woodward and another by the Spanish. A few weeks after being released from the Stuart’s Towne jail, Henry along with is his companions and about 50 armed Yamasee Indians made a trip through Georgia to the Apalachee tribes living in what is now west Florida. He had learned that the Scots had planned to contact this tribe and set up trade with them, But Woodward and his group got there first, established a trade relationship, and returned to Charles Towne with several furs and deerskins. As one historian put it, Woodward had out maneuvered the Scots.

By the following year the Spanish were growing annoyed with the Scots trespassing in Spanish Florida. In August 1686, Alejandro Thomas de Leon led a group of 150 soldiers to Stuart’s Towne, ran the inhabitants into the woods and burned the village to the ground. Several of the Scots escaped the attack, and attempted to reestablish the settlement. Most of the survivors, however, desired to return to Scotland and Stuart’s Towne was abandoned.

Over the years, the Spanish made several attempts to capture Henry Woodward as he traveled through the wilderness trading with a number of Indian tribes. He always managed to evade them although four of his companions were killed in Georgia. However, after twenty hard years of wilderness travel, the strenuous lifestyle was taking its toll.

While on a trading trip to Indians on the Chattahoochee River in late 1686, Woodward became ill. A group of Indians who revered the great trader attempted to carry him back to Charles Towne, but he is believed to have died along the way and was buried in the woods. He was 40 years old.

Henry Woodward had worked hard to be a good diplomat between the English and the many Indians he worked with. That he was valued by the Charles Towne colonists as well as the Lords Proprietors was shown in a number of ways. As mentioned before, he was given 100 pounds and a large percentage of the deerskin and fur export profits. Also, over a twelve-year period he was granted a total of 2,800 acres of land. With that he set up a plantation on Abbapoola Creek on Johns Island a few miles southwest of Charles Towne.

Although he was made deputy administrator for Anthony Ashley Cooper, and served for a time in the Charles Towne council, he did not seem interested in politics. He preferred to be free to explore new territory and set up trade arrangements with the various Indian tribes he encountered. As far as possible, he stayed out of the numerous political, religious, and economic squabbles between the factious colonists.

Henry was also well liked by the Indians he traded with. Without their help in providing food to eat as well as furs and deerskins to export to England, it is doubtful the Charles Towne colony would have survived.

It is said that he had several personal traits that proved valuable in his work as trader. To start with, he was honest. He wanted to be fair with the Indians and they respected that attitude. Unfortunately, many of his fellow traders sought to exploit the Indians and this caused a great deal of ill feeling that led to conflict and killings.

Some colonists wrote that Woodward was successful because he was adaptable to different situations and got along well just about everyone he met, including people who had different political views. He went about his business treating the Lords Proprietors, fellow colonists, and Indians with the same dignity and respect.

According to a pamphlet published in London in the early 1700s, as well as local tradition, Henry Woodward was responsible for introducing rice cultivation to Carolina. The writer of the pamphlet related that Henry was given some seed rice in 1680 by a sea captain named John Thurber who had brought it from Madagascar. The story goes that Woodward was able to grow the rice and taught others how to grow it.

Rice cultivation was successful at least partly because of the skill of enslaved Africans who had grown it in their native land. Regardless of how it began, in the next few years, rice cultivation became an enormous source of revenue for Carolina planters and Woodward is given credit for getting it started.

Henry married twice. His first wife, Margaret is believed to have died around 1675. He them married Mary Godfrey, daughter of fellow colonist, John Godfrey. With her he had two sons, John and Richard, and a daughter, Elizabeth.

It was a great loss to Carolina when Henry died. One could speculate that he could have gone on to be a peacemaker in the growing conflicts between colonists and Indians, as well as between some of the profit-minded colonists and the Lords Proprietors.

As the population of Carolina increased so did the need for land for agriculture and more settlements. Like in the rest of America, the Indians kept getting pushed back, and a number of treaties and bloody conflicts ensued as the two cultures clashed. Having lived in both the English and Indian cultures, perhaps Woodward could have worked out ways to tone down the anger that led to the Yamassee War of 1715-1717 in which hundreds of settlers and Indians died.

Woodward was an important figure in both South Carolina and American history. The accounts that he wrote of his adventures and the accounts of others about him have become important historical documents on Indian life and life in colonial America. He was obviously well respected and he accomplished a great deal in his forty years. Losing him at such a young age was significant.

Many great people have stories told about them for years. Some are true, some apocryphal. A story that has been popular since Henry Woodward’s time is that one day when he and his family were enjoying a dish of rice with black-eyed peas, his young son John was especially energetic running around the house. Henry referred to his son as Hoppin’ John and named the rice dish after him. The dish is still called that today.

One could speculate about how different the history of America could have been if more early settlers had been as tolerant and fair with the Native Americans as Woodward apparently was. Here was a man of obscure background who, from the age of twenty to forty, had an enormous impact on the growth and well-being of an important English colony. He had his flaws, of course, but they certainly did not outweigh the good he did for the twenty years he was a brave and able frontiersman. He is deserving of the acclaim he has received for over 350 years.

Ted McCormack